This article is the first in a series by FAZ Forensics intended to provide education on fraud prevention and detection, financial investigations, critical aspects in the quantification of economic damages, as well as the effective use of forensic accounting methods and techniques.

Fraudulent activity and financial disputes are already widespread in our society and vastly increasing in their frequency. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) produces an annual Report to the Nation about their global study related to occupational fraud. Occupational fraud includes cases of asset misappropriation, financial statement fraud and business corruption. The 2018 ACFE report cited 2,690 cases of occupational fraud worldwide that were reported and investigated between January 2016 and October 2017. In just the United States, during this period, the reported losses associated with occupational fraud totaled over $7 billion.

Elements of Fraud

Fraud represents a clear intersection between law and accounting…fraud is commonly understood as dishonesty calculated for advantage. A person who is dishonest may also be called a fraudster. In the US legal system, fraud is a specific offense with certain required features. Fraud must be proved by showing that the defendant’s actions involved five separate elements:

- A false statement of a material fact.

- Knowledge on the part of the defendant that the statement is untrue.

- Intent on the part of the defendant to deceive the alleged victim.

- Justifiable reliance by the alleged victim on the statement.

- Injury to the alleged victim as a result.

Fraud Theory

Fraud is a crime that is costlier than most people realize. Certain factors must be present to allow most individuals to commit these crimes. There a several theories that explain the factors that lead to fraud and other unethical behavior. Following are two of the more common of those theories. Together, the theories say that an individual’s personality traits and capability have a direct impact on the probability of fraud.

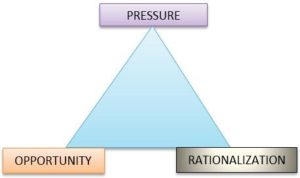

The Fraud Triangle – Developed in the 1950’s by American criminologist Donald Cressey, the fraud triangle is a three-pronged theory of fraud, whereby three factors need to be present for fraud to occur; specifically, pressure (incentive), together with rationalization and opportunity:

- Pressure (Incentive) – Usually a financial need, is often cited as the reason for committing a fraud. Depending on the context, pressures can be either personal or company based. Personal pressure may come from an individual spending beyond their means, a spouse losing a job, or gambling or drug issues. Personal pressures lead to the individual committing embezzlement or other asset misappropriation schemes. Company pressures may be the result of having to meet earnings expectations or the need for management to meet certain goals to receive compensation. These results could be achieved through financial statement fraud, such as improper revenue recognition, earnings management and other schemes.

- Rationalization – To justify their actions, the person committing fraud will rationalize such actions. These rationalizations may include: “I only borrowed the money and was intending to pay it back” or “They are a big company and won’t miss the funds” or “I’m not being paid enough in my job.” Entity-based rationalization may include: “The company won’t survive if we miss earnings again” or “We won’t get the loan if our assets don’t exceed $X.

- Opportunity – If internal controls are weak, the perpetrator may believe no one will notice if funds are taken. In many cases, the system may be tested with small amounts; and larger amounts as the expectation of getting caught becomes lower.

Figure 1: Fraud Triangle, Source: Wells J. T. (2005)

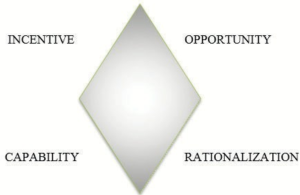

The Fraud Diamond – In the December 2004 New York State Society of CPA’s CPA Journal, David T. Wolfe and Dana R. Hermanson discussed the “fraud diamond.” The authors, added a fourth factor of capability to the Fraud Triangle, and discussed the fraudster’s thought process as follows:

- Incentive – I want to, or have a need to, commit fraud.

- Opportunity – There is a weakness in the system that the right person could exploit. Fraud is possible.

- Rationalization – I have convinced myself that fraudulent behavior is worth the risks.

- Capability – I have the necessary traits and abilities to be the right person to pull it off. I have recognized this fraud opportunity and can turn it into reality.

Figure 2. The Fraud Diamond, Source: Wolfe and Hermanson (2004)

Areas of Fraud

In addition to the defense and examination of occupational fraud, forensic accountants are involved in cases pertaining to healthcare fraud, fiduciary fraud, the fraudulent activity of third party administrators, bankruptcy fraud, computer fraud, vendor fraud, procurement fraud, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Statute (RICO), bank fraud, tax fraud, financial fraud, and foreign corrupt practices.

In the healthcare fraud arena, many cases are triggered by the False Claims Act (FCA), the Stark Law, the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) and the Criminal health care fraud statute. Additionally, Sarbanes Oxley Corporate and Auditing Accountability and Responsibility Act (SOX) the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd Frank) are relevant pieces of legislation that cause forensic accountants to be involved to help defend and investigate financial fraud.

Economic Damages and the Forensic Accountant

Some forensic accountants quantify or value the financial impact a dispute or incident may have on a business and/or individual. They help insurance adjusters and representatives understand the true economic value of submitted claims. In addition, law firms often engage forensic accountants to bring their expert knowledge to bear on difficult cases where economic damages are in dispute.

Forensic accountants work on contractual disputes, shareholder and partner disputes, intellectual property infringement matters, securities and antitrust cases, business interruption losses, subrogation actions, self-employed lost earnings calculations, and economic damages in wrongful death and personal injury, as well as wrongful termination.

In quantifying a disputed amount or a financial loss, a qualified forensic accountant will question the underlying assumptions, identify the relevant issues and thoroughly examine the detail. The measure of damages follows generally accepted methodologies. The skilled forensic accountant prepares recognized financial models to provide an estimate of the economic damages experienced resulting directly or indirectly from the wrongful act or incident. The depth and breadth of their industry knowledge and their financial acumen enable forensic accountants to really understand whether the numbers make sense and will stand up under the toughest scrutiny.

To prove economic damages in a litigation setting the experienced forensic accountant will successfully address and abide by the following legal principles:

- Proximate Cause: The recovery of damages for lost profits is subject to the general principle that damages must be proximately caused by the wrongful act or incident. This requirement is expressed in numerous cases and governs the recovery of all compensatory damages;

- Reasonable Certainty: A second requirement for the recovery of damages for lost profits is that the damages be proven with reasonable certainty. It requires that damages be capable of measurement based upon reliable factors without undue speculation. Again, this principle is expressed in many cases and is unquestionable.

- Foreseeability: There is a key question presented by cases looking for recovery of damages for lost profits on contract claims. The question is whether those damages were reasonably foreseeable as the expected and likely result of a breach of the contract at the time the contract was made.

These governing legal principles, which have been well established and reinforced by case law, should be woven into the financial analysis by the forensic accountant in a manner that shows their applicability to the case at hand. Specific supporting case law and practical approaches to demonstrate the relevance to financial models will be addressed in a future article.

Engaging the Forensic Accountant

Whether you’re dealing with fraudulent activity or a financial dispute, the positive impact of an accomplished forensic accountant can be significant. Fraud investigations and dispute resolution will often benefit from the services and skills of an experienced forensic accountant, which include: accounting, tax, general business and financial consulting, strong analytical and research skills, as well as legal knowledge. Forensic accountants also bring intellectual curiosity, professional skepticism, the attention to detail, persistence and the ability to think creatively and communicate effectively.

In addition to having the required skill set to help defend and investigate fraud and quantify financial disputes, many forensic accounting firms have developed the requisite knowledge, systems and procedures to deal efficiently and effectively in the resolution of fraud investigations and financial disputes. This will be covered in detail in future articles and will include the following areas:

- Effective Use of the Forensic Accountant

- Prevention and Detection of Occupational Fraud

- Asset Misappropriation Fraud Schemes

- Financial Statement Fraud Schemes

- Specifics and Benefits of Computer Forensics

- Criteria for Selecting a Financial Damages Expert

- Overview of Commercial Damages

- Overview of Individual Damages

- Legal Principles in Economic Damage Cases

- Mitigation of Damages Doctrine

- Anatomy of a Business Interruption Loss

- Business Divorce: Basics in Shareholder and Partner Disputes

- Fiduciary Duty and the Exposure for Fraudulent Activity

- Forensic Engagements: Acceptance and Scope of Services

- Forensic Accountant: Serving as a Consultant and/or Expert Witness

- Framework of a Forensic Accounting Investigation

- Art of the Forensic Accounting Interview Process

- Forensic Analysis of Financial Transactions

- Effective Use of Other Forensic Specialists

- Proper Communication of Forensic Accounting Findings

- Successful Expert Testimony at Deposition and Trial

- Case Studies in Forensic Accounting

Comments are closed.